color in a straight line

By Heloisa Espada

How many colors make up a neutral gray?

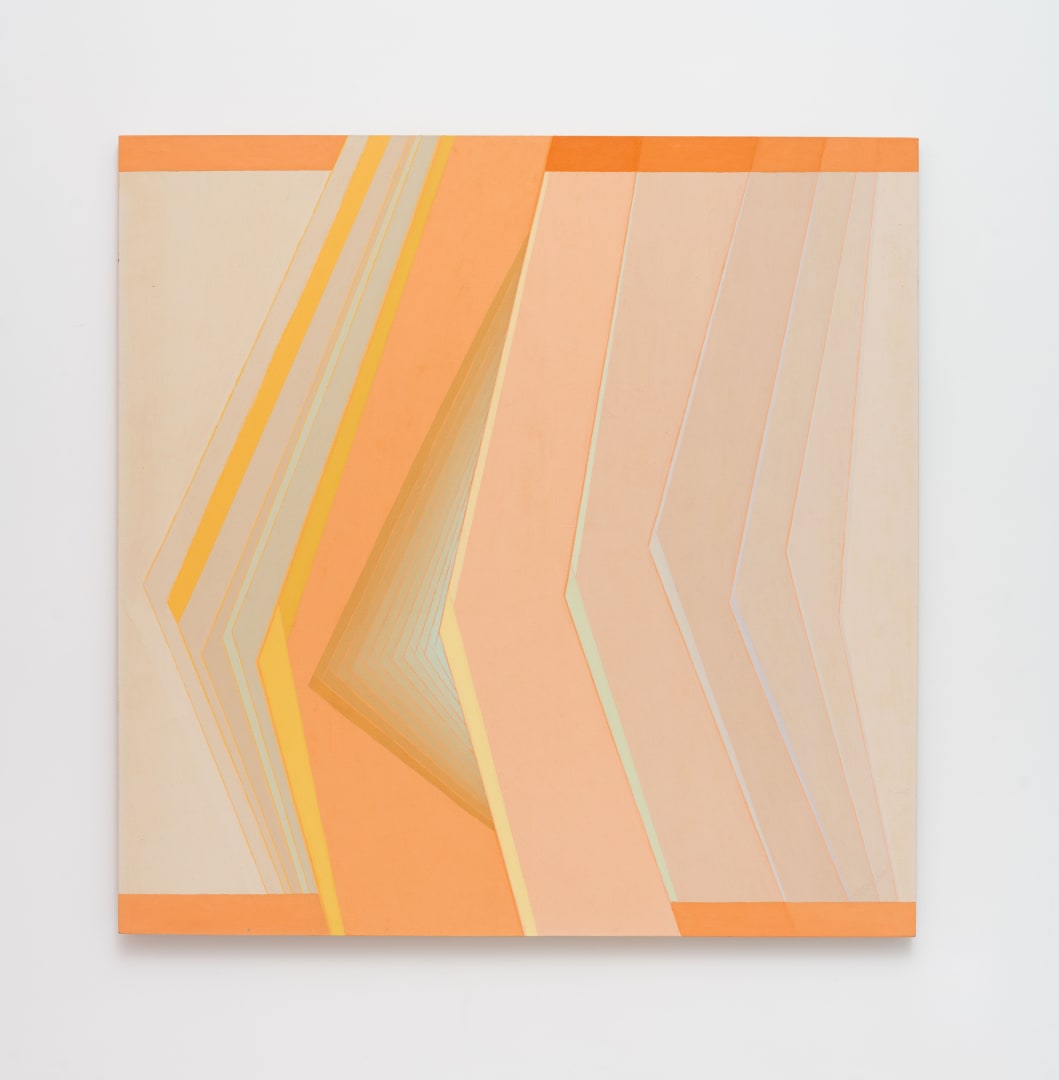

Habuba Farah (Getulina, SP, 1931) has been exploring this question for nearly seventy years. The artist tirelessly investigates the chromatic variations of the so-called 'neutral gray' or colored gray, which is obtained by mixing a primary color (yellow, blue, or red) with its respective complementary color (violet, orange, and green). Like a prism that refracts light into wavelengths of various colors, Farah's paintings reveal the potential infinity of shades contained in these highly vibrant grays by gradually adding small amounts of the primary or secondary color to the original mix. Interested in exploring extremely delicate chromatic transformations, the artist also incorporates small portions of white into the colors derived from the neutral grays.

The canvases by Habuba Farah organize a myriad tones into geometric structures that often resemble beams of light. An oil on canvas from 1963 exemplifies the process of crossing and superimposing shades from a pair of colors. In the work Untitled, 1963, the painter arranges a gradient that transitions from whitened yellow to dark brown in vertical beams. These are intersected by a series of diamonds in tones that are on the opposite end of the color scale, meaning dark diamonds intersect with light ones, and vice versa. It is no surprise that the artist refers to her paintings as symphonies. In this and other works, she envelops our gaze in cadences of the subtlest tones to disrupt the flow of consciousness with sharp and striking forms.

The artist is part of the generation that emerged in the 1950s through events organized by a series of cultural institutions established in the immediate post-war period in São Paulo. Notable among these are the São Paulo Museum of Art, inaugurated in 1947; the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art in 1949; the Biennial of the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art in 1951, and the São Paulo Municipal Library, which, at that time, under the direction of the critic Sérgio Milliet, functioned as a cultural hub, bringing together young people around its collection of art books and magazines. There is a substantial body of literature on the institutional strategies employed to promote abstractionism in Brazil within the context of the resurgence of avant-garde art on the international stage. These institutions offered courses, lectures, and exhibitions with the aim of educating the Brazilian public to appreciate modern art, and in that context, abstractionism was synonymous with what was considered most ‘advanced.’

At the time, Farah was a young artist who earned her living as a geography teacher in the city of Getulina and spent weekends in São Paulo to visit her brother, attend classes at the São Paulo Association of Fine Arts, and visit museums. After a short period, she was introduced to Samson Flexor, a Moldovan painter who had trained and worked in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s before emigrating to São Paulo in 1948, becoming one of the pioneers of abstractionism in Brazil. By attending his studio known as Atelier Abstração, where Flexor taught painting, Farah reaffirmed her preference for abstract art, which had interested her since adolescence, and she was observing in museums. During the same period, the painter also encountered and began attending the studio of Mário Zanini, an artist initially focused on landscape painting and associated with the Santa Helena Group, which also turned to abstractionism in the 1950s. In parallel, she started exhibiting her own abstract work at various editions of the São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, held at the Prestes Maia Gallery, and in exhibitions organized by the São Paulo Association of Fine Arts.

Since those early years, Farah has consistently worked with painting, drawing, and collage, focusing on chromatic research around the ‘neutral gray,’ often combined with geometry. Over the decades, she exhibited her works both in Brazil and abroad and maintained connections with critics and intellectuals interested in her practice, such as José Geraldo Vieira, Theon Spanudis, and Mario Schenberg. However, recognition of her work within the national art system came late. Like many women artists, after getting married and having two children in the 1960s, Farah had to balance her time between artistic production, family life, and teaching art classes from the 1960s to the 1980s at her home in São Paulo. Given the substantial body of work she produced during these years, it appears that she chose to deepen her pictorial investigations rather than focus on promoting a professional artistic career.

"Composition is the art of arranging in a decorative manner the diverse elements at the painter’s command to express his feelings," [1] wrote Henri Matisse in 1908 when arguing that the expressiveness of a work primarily resides in the relationships between the visual elements such as shapes, colors, and lines. In the early days of the history of abstraction in the West, the association between abstraction and decoration was not regarded as frivolous but as the exploration of a free territory for formal experimentation, which was previously constrained by the commitment to representation. Within this context, abstract art was often seen as the logical consequence of modern art itself, given that modern art was characterized by the autonomy of visual arts from the depictions of the world.

Paradoxically, in Western tradition, the invention of abstraction was linked both to the expression of an individual spiritual need (as in Kandinsky's conception, for example) and the development of science. Science enabled new ways of seeing the world through inventions like electric light, automobiles, microscopes, and airplanes. In other words, in the history of modern art, abstraction was explained in both metaphysical and material terms (given that modernity gave cities an abstract appearance). Modern art was explained as both the ultimate expression of individualism and the manifestation of a universal language. It is worth noting that today the claim of universality in modern art is understood as a strategy of cultural colonization and the assertion of Western power over other peoples. The criteria for what was considered ‘civilized’ and ‘universal’ was set by white European men. Nevertheless, different forms of abstraction, linked to diverse cultural traditions, continue to be present in contemporary production.[2]

In its breadth and diversity, Farah's work draws connections to the aims of early 20th century European artists while constituting a research project that established its own parameters and objectives in the process. Initially inspired by the 19th century studies of the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul on color perception, Farah developed her own theory known as The Neutrals of Color Theory. Chevreul's ideas, documented in his book On the Law of Simultaneous Contrasts, were influenced by Impressionist painting and had an impact on Georges Seurat's divisionism. In essence, the French scientist concluded that color perception depends on a chromatic context, meaning that green will appear more vibrant next to red than next to blue. Similarly, black will appear intense and consistent when placed next to light colors but will appear faded next to browns and other dark tones. Farah used Chevreul's law of simultaneous contrasts as a foundation to arrive at her neutral grays. As mentioned earlier, the artist then created new shades by adding drops of white into the countless tones present in her grays.

The connection with Chevreul is evident in the works of the series Oposta [Opposed] from 1973, where the painter creates intense chromatic contrasts through the juxtaposition of shapes and hues. In one of the paintings in the set, Farah overlaps gradients ranging from yellow to dark purple, almost black, passing through oranges, reds, greens, and browns. The work evokes the level of freedom and experimentation sought by Matisse when investing in the decorative character of modern art. In it, Farah constructs two porous and open squares, combining the opposing notions of continuity and contrast, cohesion, and suspension.

Habuba Farah's solo exhibition at Gomide & Co gallery brings together works created between 1950 and 2023 for the first time. Given that light propagates in a straight line, at this show, geometry emerges as the most suitable means to bring order to the artist’s extensive chromatic research focused on the interplay of tones and contrasts. With a keen eye for the combination of light and form, Habuba Farah explores the boundless through painting.

Heloisa Espada is a professor of Art History and curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of São Paulo.

[1] MATISSE, Henri. Notas de um pintor, 1908. In: CHIPP, H. B. Teorias da arte moderna. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1999. p. 128.

[2] Currently, the exhibition Direito à forma [Right to Form], curated by Deri Andrade, Igor Simões, and Jana Janeiro, on display at Inhotim, showcases works by thirty contemporary Black artists who work with abstraction.