Bergamin & Gomide paritcipates in Art Basel OVR: 20c presenting "The mystery of living things", dedicated exclusively to works created during the 20th century, from October 28th to 31st, 2020, on Art Basel's online platform.

We feature works by Amadeo Luciano Lorenzato, Amélia Toledo, Francisco Brennand, Frans Krajcberg, José Resende, Marcelo Cipis, Mira Schendel, Montez Magno, Oswaldo Goeldi and Rivane Neuenschwander. A selection of works that stem from natural elements or from the observation of the diversity characteristic of the Brazilian territory. They are works that seek to bypass the mystery of living things and to offer this fundamental experience which is the contact with nature.

The word nature, in its Latin origin natura, designates what will be born. Throughout our existence we are constantly impressed by its power and self-sufficiency, with its spontaneous beauty and the teachings that nature brings us, after all, we were born and grew in it. If for Man art is a timeless manifestation of its own essence, it is not surprising its constantly returns to this universe and its meanings.

From the sculptural mangrove by Frans Krajcberg, to the shells collected on the coast by Amelia Toledo, to José Resende's mineral abundance, the works seek to bypass the mystery of living things; that stem from natural elements or from the observation of the diversity characteristic of the Brazilian territory.

Frans Krajcberg (1921-2017) claimed the “sensibility of the natural”. This was the leitmotiv of his work: “I cannot go into the middle of the street and start yelling,” he says, “otherwise I’ll be arrested or taken to the hospice. But, when I recover these burnt tree logs devastated by men’s violence and use all the expressivity that they bring to create, I show their scream.” For this reason, his work is mostly made of curved wood, whose expressivity of curves and twists figures as a manifesto.

José Resende (1945) in exercising the difficult balance of two small stones connected to a base stone by iron bars – presents three similar and interconnected elements whose forms are not repeated. With this work, which has discreet dimensions if compared to a large portion of Resende's production, we have a beautiful example of the autonomy and synthesis exercised by the artist throughout his career. José Resende's work teaches us about the disengagement with immediate communicability, since he pursuits the artistic language as a condensed power.

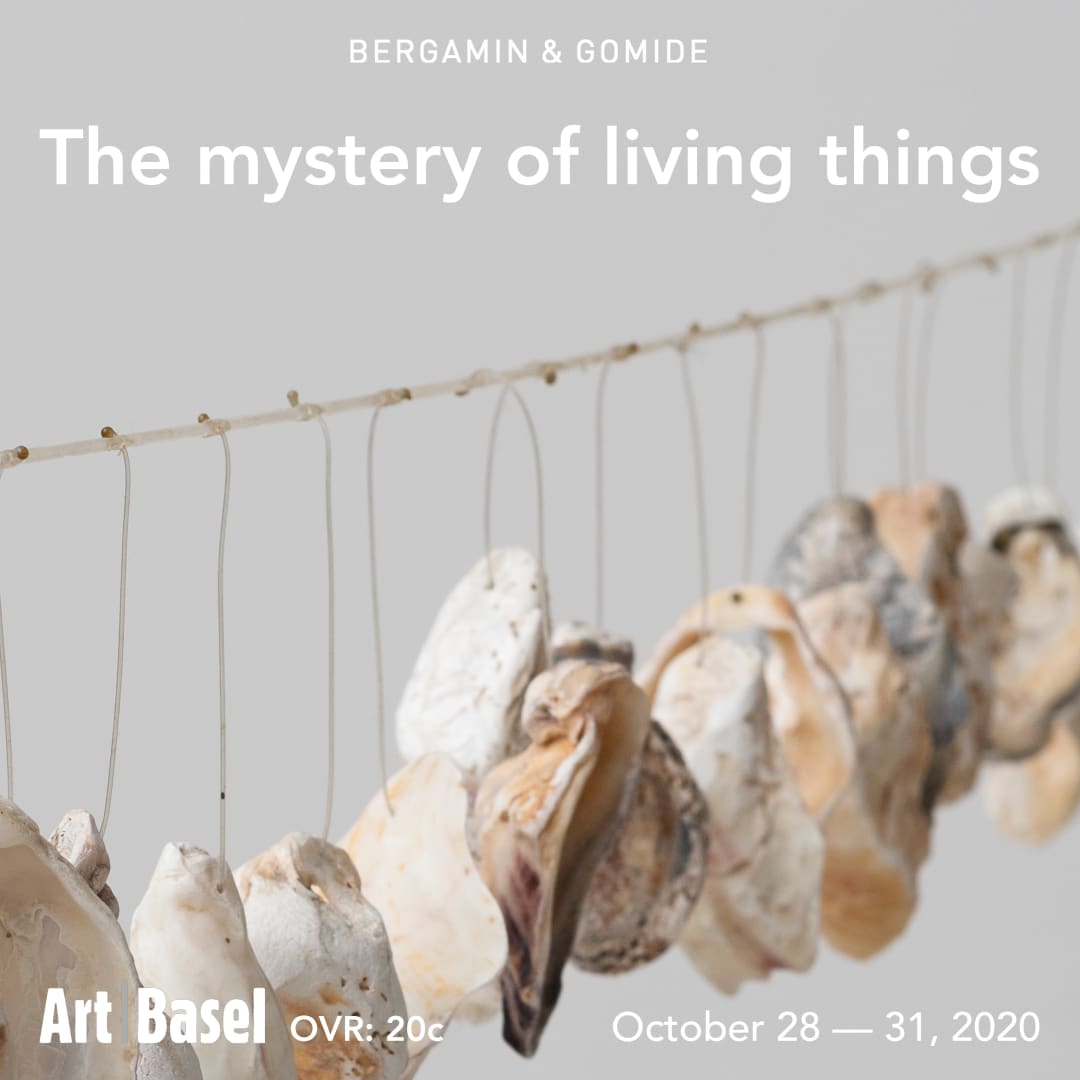

Amelia Toledo (1926-201) departs from her experiences in Rio de Janeiro when she walked the beach collecting shells in the sand, which resulted in the creation of several works, among them Gambiarra (1976): a clothesline made with nylon threads and sonic shells organized in such a way as to dance and play with the wind. In this work, the artist attributes new functions and potentialities to these natural elements that are the shells, by aligning them in a way that contrasts with the randomness present in nature.

Francisco Brennand (1927-2019) vitrified ceramics flirt with a kind of biomorphic abstraction in which the rounded forms resemble the human body, animals and elements present in nature. Regarding the actual piece selected, the figure that emerges from a round basis extends itself without representing anything specifically – but maintaining the dialogue with the phallic forms that are repeated throughout Brennand’s production in works of various dimensions, whether monumental or simple like this one.

Rivane Neuenschwander (1967) exhibited her leaves for the first time at the Second Johannesburg Biennale in 1997, together with another work in which the artist created a carpet of apeiba tibourbou seeds glued together. At that time, the artist lived in London and her artistic practice was focused on working with natural elements such as dried leaves, garlic peels, ants, among others things. In the works concerned, Rivane dissects the leaves in order to highlight their structure, that is summarized in lines and contours that call attention for their delicacy.

By bringing together these works of art, perhaps we can contribute to a “subjective depollution” necessary for an objective change that must be undertaken in the world, as Krajcberg, Pierre Restany and Sepp Baendereck conceived in their Manifesto do Rio Negro in 1968:

“It’s about fighting against certain ecological perspectives. It’s about fighting much more against subjective pollution than against objective pollution, against the pollution of the senses and the brain, much more than of the air or water.”